DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7762894

The Barberini Harp at the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali (Fig. 1 ).

A harp commissioned by the influential aristocratic Barberini family was built in Roma, probably in 1632. It remains preserved to this day as one of the most valuable Italian musical instruments of the 17th century: the “Arpa Barberini,” an elaborately made instrument with a magnificent carved and gilded column. It bears the Barberini coat of arms and other symbolic decoration. Soon after the harp was made, the Roman painter Giovanni Lanfranco (1582-1647) immortalised the instrument in a painting, suggesting special appreciation for the harp in the artistic circles around the Barberini pope Urbano VIII (Maffeo Barberini, reign 1623-1644).

Privately owned for a long time, the instrument thus survived the passage of time; it was not handed over to the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali in Roma until the early 1970s. It remains in the museum’s collection today, though it can no longer be played for conservation reasons.

Despite its undisputed historical value, the “Arpa Barberini” is far from having been adequately researched. For this reason, an interdisciplinary conference was held at the Istituto Storico Austriaco [Austrian Historical Institute] in Roma in December 2016 at the initiative of the Berlin-based harpist Margret Koell. Harpists, instrument makers, musicologists and art historians from several countries met, discussed problems and questions relating to the Barberini Harp and explored the possibilities of creating an exact copy of the instrument.

Istituto Storico Austriaco, some of the Convening participants (Fig. 2 ).

The Convening began in the afternoon of December 14, 2016, with the participants gathering in the exhibition room of the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali, where the Barberini Harp is kept. Following opening remarks by the initiator Margret Koell and the museum director Sandra Suatoni, an extraordinary concert was held. Only a few metres from the original Barberini Harp, three copies of the instrument were set up: by David Brown (made in Baltimore in 1989), by Dario Pontiggia (in Milano, 2006) and by Eric Kleinmann (in Rangendingen, 2005). Mara Galassi (Milano), Chiara Granata (Milano) and Loredana Gintoli (Berlin) played 17the century compositions on these harps in an homage to the Barberini Harp.

Istituto Storico Austriaco, Steinheuer with the three interpretations of the Barberini Harp, from left: by Dario Pontiggia, David Brown and Eric Kleinmann (Fig. 3 ).

Using excerpts from letters, Alexandra Ziane (Wien) then reconstructed the efforts in the late 1960s by the American curator Emanuel Winternitz (1898–1983) to transfer the Barberini Harp from a private Italian collection to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Arts. Ziane’s presentation was followed by a tour of the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali with the director Sandra Suatoni, including the newly designed area that was not yet open to the public.

15 December 2016 / morning session

The next morning, harpist and researcher Chiara Granata and harp maker Dario Pontiggia presented the current state of research on the Barberini Harp. As part of her research in the Archivio Barberini at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Granata was able to prove that a harp was built in 1632-33 on behalf of cardinal Antonio Barberini for the composer and harpist Marco Marazzoli. It is very likely that this is the Barberini Harp, especially as older dendrochronological investigations dated the wood of the soundbox to between 1605 and 1610. However, Chiara Granata also pointed out the differences between the surviving instrument and the depiction of the harp in Lanfranco’s painting, which exist in a number of details (including colour, shape, and position of the sound holes, and more).

Chiara Granata presenting at the Istituto Storico Austriaco (Fig. 4 ).

Ursula Verena Fischer Pace (Roma) then situated the design of the Barberini Harp within the art-historical context of Roman culture in the first decades of the 17th century. Fischer Pace presented a drawing by the Roman architect Giovanni Battista Soria (1581–1651), depicting a model for a harp. This resulted in a very lively discussion about the meaning of the gilded figures on the harp’s column. Three carved male figures can be seen in the middle and directly above them two clearly younger boys draped in lion skin. Florian Bassani (Bern) suggested the following interpretation for this pictorial programme: the three male figures represent the pope’s three nephews Francesco (1597-1679, cardinal), Taddeo (1603-1647, prefect of Roma, prince of Palestrina) and Antonio (1607-1671, cardinal). The two boys represent the two sons of Taddeo (i.e. the pope’s great-nephews), who were born just when the harp was built: Carlo (1630–1704, cardinal) and Maffeo jr. (1631–1685, prince of Palestrina). The lion skin could be an allusion to the ancient hero Hercules, symbolising the great power and inviolability of the Barberini papal family.

The art historian Elisabetta Frullini (Roma/Wien) took Giovanni Lanfranco’s famous painting “Allegory of Music” as the starting point for her presentation. Frullini pointed out the important role played by Marco Marazzoli as the Barberini court musician, and presented comparable paintings.

Giovanni Lanfranco, Venere che suona l’arpa or La Musica (Fig. 5 ).

15 December 2016 / afternoon session

The discussion turned to specialist organological and historical issues. Dinko Fabris (Roma) dedicated his presentation to Luca Antonio Eustachio, who is described in Marin Mersenne’s Harmonie universelle (1637) as the inventor of the “arpa a tre ordini.” Eustachio came to Roma from Apulia and was in the service of pope Paolo V of the Borghese family. Many documents mention him as a musician, without specifically mentioning his role in the development of the triple harp. Patrizio Barbieri (Roma) then devoted himself to harp and harpsichord models in which a distinction is made between enharmonic semitones.

Istituto Storico Austriaco, participants (Fig. 6 ).

The day concluded with Harp Laboratory: the harpists Margret Koell, Mara Galassi, Loredana Gintoli and Chiara Granata performed the same piece on four different harps. The resulting differences in sound were then discussed in a plenum.

16 December 2016 / morning session

The morning of December 16th was primarily reserved for the harp makers and string makers. David Brown used numerous illustrations and descriptions in order to situate the Barberini Harp within the history of harp making in the 16th and 17th centuries. He also evaluated the X-ray images of the Roman instrument.

Istituto Storico Austriaco, discussion (Fig. 7 ).

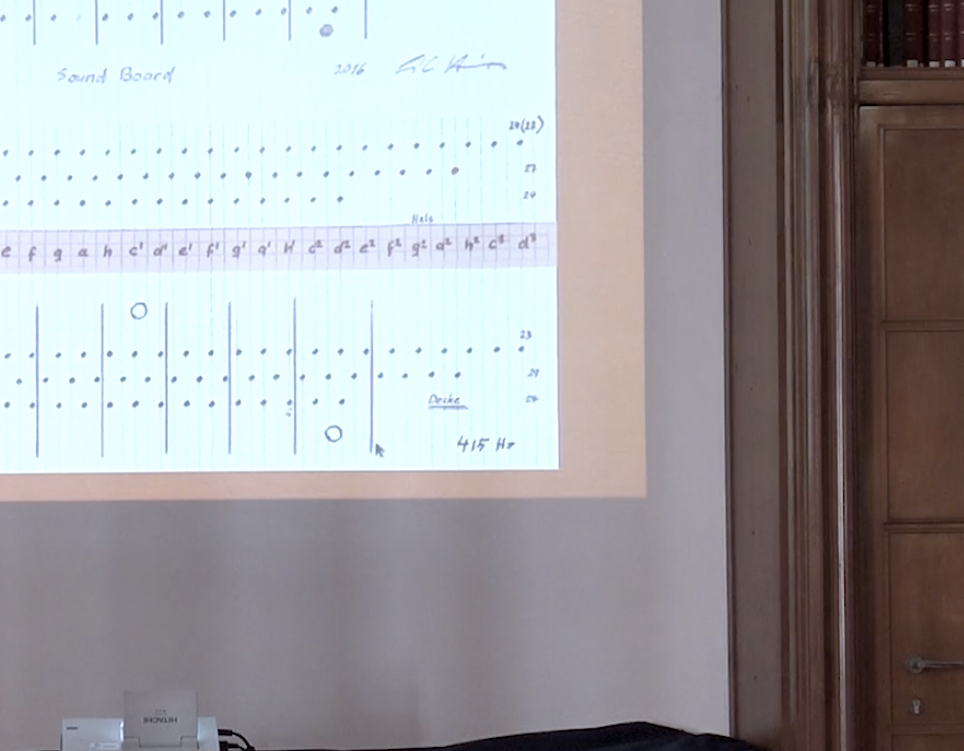

Eric Kleinmann then gave a detailed account of some of the Barberini instrument’s unanswered questions. He put forward the thesis that the change in the attachment of the strings was probably carried out in order to raise the pitch from the original a1=392 Hz. In addition, two low strings were added during a 17th-century remodelling, further hollowing out the neck at this point. The lowest string may not have been playable at all, coming too close to the elaborate decoration. Eric Kleinmann also presented photos of the interior of the harp’s soundbox, taken with a 360-degree camera. The “inner workings” of the Barberini Harp could thus be clearly seen for the first time. Finally, he raised the possibility that the harp’s soundboard might have been replaced at an early stage, which would in turn explain the differences with Lanfranco’s painting. According to Kleinmann, it is still unclear which wood was used in the making of the column.

Strings on the Barberini Harp (Fig. 8 ).

String maker Mimmo Peruffo (Vicenza), offered his expertise in pointing out the possible nature of the strings on the Barberini Harp. In his experience, the string breaking point is at frequencies of and above 260 Hz per metre.

Adam Lowe from Madrid was then included in the conversation via Skype, to talk about the complex 3D scan of the Barberini Harp he made with his team from FACTUM arte. The Convening participants were able to see an account of this process, in a short film and photographic prints by Studio Armin Linke, shown on the previous day. The external appearance of the instrument can be precisely reconstructed following the 3D scan.

16 December 2016 / afternoon session

The afternoon lectures moved the focus back onto musico-historical topics and were devoted to possible interpreters and the presumed repertoire performed on the Barberini Harp. Alexandra Ziane introduced the many harpists who were active in Roma at the beginning of the 17th century, with a particular emphasis on Orazio Michi, whose playing was mentioned in several sources. Joachim Steinheuer (Heidelberg) considered the possible repertoire of the corresponding period, indicating the harp as an ensemble instrument, as well as a basso continuo and a solo instrument—an evaluation based on both written and iconographic sources. Finally, Florian Bassani mentioned in his lecture the use of harps in Roman sacral music and evaluated contemporaneous tracts for indications of harp repertoire. Accordingly, there was little idiomatic solo literature for the harp in Roma of the early 17th century. Instead, the harp was considered (by Agostino Agazzari, for example) as an ensemble and bass instrument. However, improvising on bass models was an essential part of making music at the time, which could also include the harp as a solo or melody instrument.

Istituto Storico Austriaco, Convening participants (Fig. 9 ).

In the final discussion, the current state of knowledge about the Barberini Harp and ideas on a possible exact replica were exchanged again. It became clear that despite the extensive technical aids such as 3D documentation and X-rays, each of the three harp makers present would make different artistic decisions. Overall, the symposium in Roma was felt to have been very useful, informative and collegial by all participants. They indicated as very desirable a continuation of the project through an accompanying publication and the construction of an exact replica.

Cite:&&Bernhard Schrammek, “Report on the Convening in Roma 14-16 December 2016," Harfenlabor.com, May 20, 2021, https://www.harfenlabor.com/research/report-on-the-convening-in-roma-14-16-december-2016/.