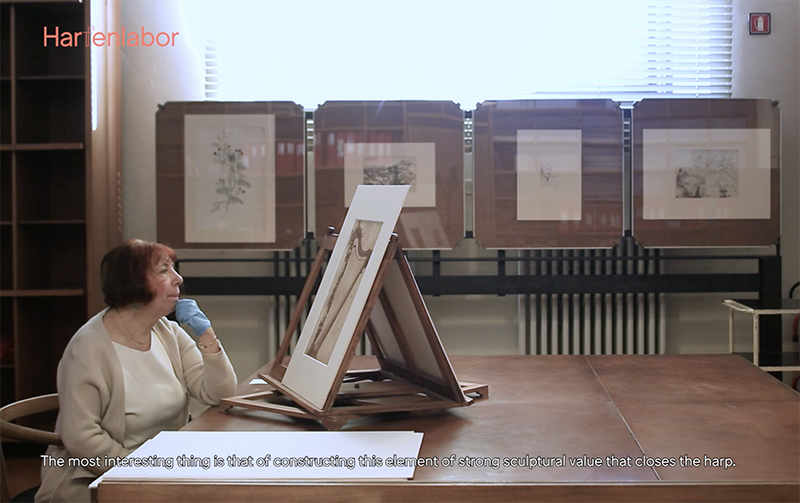

Synopsis: Marzia Faietti, the former director of the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe at Gallerie degli Uffizi, shares insights into the origins of the Uffizi's remarkably old and intact collection of graphic art and the representation of musical instruments within it. The figures of Orpheus and King David dominate these representations across various schools and artistic languages. Faietti explains why it is often difficult to attribute works clearly in the context in which artists were exposed to many different influences. The importance of music was such that some artists, like Pietro Candido, have developed techniques that “immerse" the viewer in music, “make it vibrate" on the paper. Faietti offers insight into the practices of the time on the example of Marcantonio Raimondi engraving for Raffaello. Clearly, the artists of the time were very familiar with music instruments, as they depict the instruments of their time. Graphic art of the period overlaps with design, as demonstrated on the example of the drawing titled <i>Progetto per un’arpa</i> (often attributed to Giovanni Battista Soria). Faietti focuses on the drawing as one of the preparatory drawings for a sumptuously decorated harp, and an exquisite example of the strong closeness of the various arts involved in such a project. This drawing is believed to be a preparatory drawing for the Barberini Harp, now preserved at the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali, Roma. Faietti’s art historical and iconographic analyses of the works in the collection, of their context and provenance, structure a rich interpretation of the aesthetic, musical, political, ceremonial and economic importance of precious historical musical instruments such as, in particular, the Barberini Harp.

+

Marzia Faietti

Marzia Faietti provides art historical context for music iconography and its relation to mythological figures within the graphic art of the 16th and the 17th century at the Uffizi. Faietti's analysis of a preparatory drawing for a richly decorated harp, often attributed to Giovanni Battista Soria, offers a fascinating insight into the aesthetic, political, musical, ceremonial and economic importance of such an instrument.